My First Project¶

Goal¶

The Kabaret framework covers many aspects of a TD needs. The most valuable one is probably to build a pipeline and/or workflow for the artists.

Without getting too much in depth into this topic, we are going to give you a hit of what if feels like to build something with kaberet.flow, the package responsible for making this task a pleasure.

Prerequisites¶

For this tutorial we assume that you have successfully walked through the previous one and that you can run a Kabaret standalone session.

Preparation¶

Get comfy, we need to talk before the fun.

Kabaret’s solution to develop pipelines and workflows is named Flow and is available in the kabaret.flow package. The reasons why kabaret.flow is outstanding are beyond the scope of this tutorial, but you should know that one of them is that it’s really simple to understand and to use.

The idea is to define a schema of your project using objects and relations between them. That’s the whole concept. Nothing more. Anything done with the flow is just some objects related to each other.

kabaret.flow provides a list of different relations and a few specialized object types. You will extend those objects and use the existing relations to create the schema of your project. This is often related to as project “modeling”.

- Here are the kinds of objects at your disposal:

- Objects are the base for everything.

- Values are Objects that hold data.

- Maps are Objects containing a dynamic list of Objects.

- Actions are Objects that execute code.

- The most often used relations are:

- Parent: the related Object contains this Object

- Child: the related Object is inside this Object

- Param: the related Object is a Value

We are going to use those Objects and Relations to model a really basic project consisting of just a list of shots. let’s create this module in our studio:

<BASEDIR>/my_studio/my_first_flow.py

We will write all this tutorial code in this file. The complete code can be seen here.

Note

In real life situation we would probably define our project in a package instead of a module, and it would be a good choice to have all the projects in one package like: my_studio.flows.my_first_flow

Let’s play !¶

Now grab your favorite mechanical keyboard, we’re diving in !

Foreplay¶

A project is defined by a root Object that contains all other Objects. Our project will consist of a list of Shots and a few settings values. Let’s add a basic structure for that:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 | from kabaret import flow

class Shots(flow.Map):

pass

class ProjectSettings(flow.Object):

pass

class Project(flow.Object):

shots = flow.Child(Shots)

settings = flow.Child(ProjectSettings)

|

Flow code is easily read from bottom to top. Let’s walk through this code in this order.

The Project class is our project definition. It’s a flow.Object extended with two Child relations: the shots and the settings. The Child relation means that Project “contains” shots and settings.

The ProjectSettings class is a bare flow.Ojbect. We will use it to group settings values.

The Shots class is a flow.Map. A Map can store several objects. We will use it to store our shots.

Let’s see how it looks in your application. Start it, create a new project with the name “MyFirstProject” and the type “my_studio.my_first_flow.Project”. After entering the project you should see something like this:

Hmm… You might not be impressed yet :p

Ok so if you’re not impressed by the GUI built with 8 lines of code, let’s see two sugar features of the flow package now. Don’t close your application, but go on and swap order of shots and settings in the Project class and save the file:

12 13 14 15 | class Project(flow.Object):

settings = flow.Child(ProjectSettings)

shots = flow.Child(Shots)

|

Now in the “Option” menu at the top-left of your flow view, select “Activate DEV Tools”. A new “[DEV]” menu should appear. In this menu select “Reload Project Definitions”. And voilà !

The order you define your object relations is reflected in the GUI. And you don’t need to restart your application to see your changes. We’re going to use that a lot !

Now let’s keep it nice and swap back those two relations please…

Using Values¶

It’s time to add some values to the ProjectSettings.

All our shots will contain some files, so we’re going to need a place to store them. We will be using a Param relation to let the user edit this location and a few IntParm for things that would make sense in a real world scenario:

8 9 10 11 12 13 | class ProjectSettings(flow.Object):

store = flow.Param('/tmp/PROJECTS')

framerate = flow.IntParam(24)

image_height = flow.IntParam(1080)

image_width = flow.IntParam(1920)

|

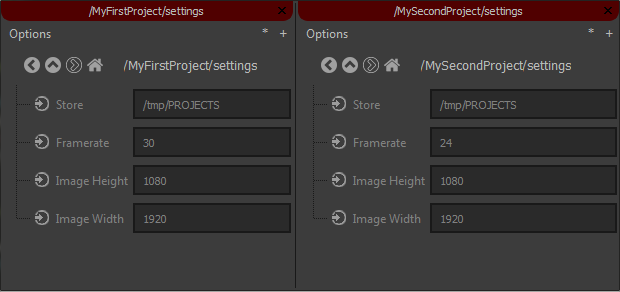

Now click [DEV] -> Reload and open the Settings field.

All fields show the default value defined by our code. If you edit the Store field you will see a blue background until press enter and the new value is stored. If you edit the frame rate and try to input something else than an integer, a red background appears in the field: your value was rejected. All those fields accept python expressions so you can enter 3*10 in the Frame Rate field and the result will be stored.

Now run another instance of your application and browse to MyFirstProject/settings. Change a value and see how the first application reflects the change without any intervention. This works for every instance of your application in the local network.

And now let’s click the home button and create a project “MySecondProject” with the same type “my_studio.my_first_flow.Project”. Browse to its Settings and witness how this project uses the default values. You can duplicate the current view by clicking the “*” button on the upper-right corner, and use the new view to show both projects settings side to side:

Hmm… Should you be impressed ?

Now is the time to realise something crucial about Kabaret’s Flow: The thing you are modeling is not the project itself but the schema of your projects. In fact, your projects are instances of your flow. It is a complete different approach than connecting nodes in Nuke or in Maya where you define a graph that is used as a dataflow. Here we are defining a graph that generates the graph that will (or may) be used as a dataflow. Each instance of your flow has its own set of values, but the structure is shared. If you comment the framerate relation in your ProjectSettings class and reload your Project Definitions (on both views), you will see that neither MyFirstProject not MySecondProject contains a framerate field anymore. Another nice feature is that if you un-comment this line and reload, both projects will have their previous value back. And maybe the nicest part is that you did all this without having to worry about how to store the values, and without enduring some migration process to alter the schema of your data. Welcome to the 21st Century ! ;)

Defining the flow instead of the actual project is something borrowed from the “Workflow” world. It has many advantages among which the fact that when you add something, for exemple a batch process between two tasks of a shot, everything is updated at once: all shots will contain this process without the need to update existing graphs or trigger some dark-magic synchronisation machinery.

Now let’s forget about MySecondProject and focus on building something more interesting.

Using a Map¶

We’ve seen how we are defining a structure instead of a concrete project. But all our projects won’t have the exact same structure. In our case - a simple shot manager, the list of shots will need to be different from project to project. We can’t just use something like:

class Project(flow.Object):

shot001 = flow.Child(Shot)

shot002 = flow.Child(Shot)

shot003 = flow.Child(Shot)

shot004 = flow.Child(Shot)

shot005 = flow.Child(Shot)

That’s the reason for the kabaret.flow.Map to exist: It provides a per-instance list of things. Let’s see how by implementing a few methods on our Shots class:

4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | class Shot(flow.Object):

first = flow.IntParam(1)

last = flow.IntParam(100)

class Shots(flow.Map):

@classmethod

def mapped_type(cls):

return Shot

def columns(self):

return ['Name', 'Ranges']

def _fill_row_cells(self, row, item):

row['Name'] = item.name()

row['Ranges'] = '{}->{}'.format(item.first.get(), item.last.get())

|

We added the Shot class definition. It’s a simple object with two Params. We also implemented the Shots’ mapped_type classmethod to return our Shot class. This tells the flow that all objects contained in the Shots map will be Shot objects (or subclasses of Shot).

We have also overridden the default implementation of the columns() and _fill_row_cells() methods. Both are used to configure the information displayed in the views. The Shots map will now list the name and the ranges of each shot it contains.

You can notice how _fill_row_cells() gets the value from the Shot item it receives. We know the item argument is a Shot because we configured the Map for that. The Shot class has a first and a last relation, so every Shot instance has a first and a last attribute containing the respective Value Object. Every Value in the flow has a get() method that returns the data it holds.

Next step is to add some shots in the Shots map, and we will need user input for that.

Using Actions¶

Pipeline is not all about metadata, it is about executing code too. Sometimes the code has to be triggered by some event, sometimes it is up to the user to trigger it. The kabaret.flow.Action Object is meant for this second case.

An Action will show up in the GUI as a button and/or as an entry in a menu. By clicking it, the user tells the action to show a dialog if needed, and then execute its run() method. Let’s add an Action that creates a Shot in our Shots Map:

class AddShotAction(flow.Action):

def get_buttons(self):

return ['Create Shot', 'Cancel']

def run(self, button):

if button == 'Cancel':

return

# create the shot here

You create your own Action by extending the flow.Action class. The get_buttons() method can be implemented to return the list of buttons available in the Action’s dialog. When the user clicks one of those buttons, the run() method is called with the name of the clicked button. Our run() implementation checks that the clicked button was not “Cancel” before doing anything.

In order for this Action to be used by our flow, we need to add it as a relation somewhere. As it will act on the Shots map, let’s make it a Child there:

class Shots(flow.Map):

add_shot = flow.Child(AddShotAction)

...

If you reload your project definitions you will see a new menu button on the right of the Shots label. This menu contains the “Add Shot” entry. Clicking it will show a dialog with the “Create Shot” and “Cancel” buttons.

Now let’s implement the run() method to actually create a Shot. The flow.Map Object has an add() method accepting a string as the name of the item to add. We will need to call it with a user input value. This input will be handled by a Param in the AddShotAction. And, as the Action is a Child of the Shots Map, we will use a Parent relation to access the Shots from within the AddShotAction:

class AddShotAction(flow.Action):

# The leading _ tells the GUI that this relation is protected

# and should not be shown:

_shots = flow.Parent()

# Params will show up in the Action dialog:

shot_name = flow.Param('shot000')

first_frame = flow.IntParam(1)

last_frame = flow.IntParam(100)

def get_buttons(self):

return ['Create Shot', 'Cancel']

def run(self, button):

if button == 'Cancel':

return

# Real life scenario should validate this value:

shot_name = self.shot_name.get().strip()

# Create the shot using our Parent() relation:

shot = self._shots.add(shot_name)

# Configure the shot with requested values:

shot.first.set(self.first_frame.get())

shot.last.set(self.last_frame.get())

# Tell everyone that the Shots list has changed

# and should be reloaded:

self._shots.touch()

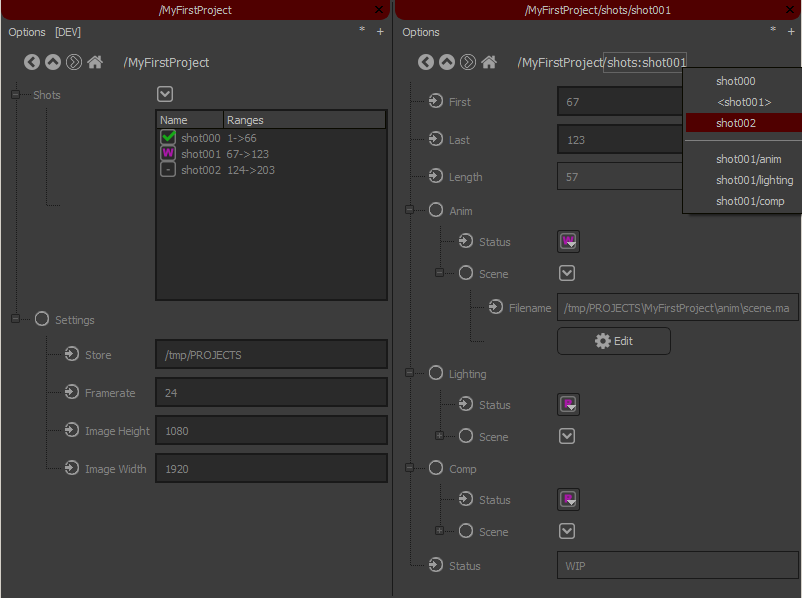

If you reload your project definitions you will now be able to create some shots and even configure them on the fly. A Shot can be browsed by double-clicking on it. CTRL+DoubleClick will open it in a new view.

Computed Value¶

We discussed earlier the fact that the kabaret.flow borrows ideas from the Workflow principles to overcome issues arising when using dataflow to represent a project pipeline. But there’s still great power to harvest in dataflow, especially in lazy evaluation dataflow (a.k.a pull dataflow). At some point you will probably want to manage some Value holding the result of a computation using other Values. And this computation should occur when needed (when a dependent Value changes for exemple.)

We will showcase such a need by adding a length Value in our Shot class. This Value is computed using the first and last Params, and is updated every time one of them changes.

This is done using the Computed Relation. This Relation defines a Child ComputedValue in the parent Object. The parent Object is responsible for the computation of this Value.

Let’s add a length Computed relation to our Shot class, along with an implementation of is compute_child_value() method:

class Shot(flow.Object):

first = flow.IntParam(1)

last = flow.IntParam(100)

length = flow.Computed()

def compute_child_value(self, child_value):

'''

Called when a ComputedValue needs to deliver its result.

'''

if child_value is self.length:

self.length.set(

self.last.get()-self.first.get()+1

)

If you reload your project definitions, you will see the new “Length” field in every Shot. And it has the correct value, great !

But if you change the first or the last value of the Shot, the length does not update. Let’s fix this by specifying that we want to react to changes on first and last. This is done by configuring their relation and implementing child_value_changed():

class Shot(flow.Object):

first = flow.IntParam(1).watched()

last = flow.IntParam(100).watched()

length = flow.Computed()

def child_value_changed(self, child_value):

'''

Called when a watched child Value has changed.

'''

if child_value in (self.first, self.last):

# We invalidate self.length whenever self.first or self.last

# changes:

self.length.touch()

def compute_child_value(self, child_value):

'''

Called when a ComputedValue needs to deliver its result.

'''

if child_value is self.length:

self.length.set(

self.last.get()-self.first.get()+1

)

If you reload your project definitions you will notice that the Length fields shows an updated value whenever you change the value of the First or Last field.

Divide, Compose and Conquer¶

Another advantage of kabaret.flow is how it helps you divide your pipelines into components and layers.

A classical dataflow let you encapsulate logic into nodes and connect them together. This is a great way to isolate concerns into components, which is easier to develop, test and manage.

With kabaret.flow you can go even further by defining Objects composed of other Objects. It’s like having a dataflow inside each node of your dataflow. It gives you the ability to not only isolate concerns into components, but also to encapsulate and compose them into new components. You’re actually layering responsibilities, which is known as the good architecture when building complex software.

We are going to illustrate this by adding some content to our Shot Object.

Let’s say that a Shot is composed of consecutive tasks, and that a task has a status and a file that contains the work done for that task. It’s an oversimplified case for a CG Pipeline, but it already contains two clearly separable concerns: file naming conventions (Persistence Layer), and task status (Business Layer).

We’re going to lay down the structure for that:

class File(flow.Object):

pass

class Task(flow.Object):

status = flow.Param()

scene = flow.Child(File)

class Shot(flow.Object):

first = flow.IntParam(1).watched()

last = flow.IntParam(100).watched()

length = flow.Computed()

anim = flow.Child(Task)

lighting = flow.Child(Task)

comp = flow.Child(Task)

...

We’ve added some tasks to the Shot. Each Task has a status Value and a scene object which is a File.

Reload and you will discover a whole hierarchy in MyFirstProject. This hierarchy is your Workflow/Pipeline (Business Layer). It is encapsulated in the Project component. This component uses the Task component, which is also in the Business Layer. The Task uses the File component which is in the Persistence Layer.

Now you that we’ve clearly separated concerns, we can implement their functionalities and behavior.

The purpose of the File is to provide a filename. This filename is not to be edited by the end user. It must be provided by an authority responsible of applying naming conventions. Let’s implement a very simple strategy which consists of a single function that turn some parameters into a filename. This function will be used by a ComputedValue in the File:

import os

...

class File(flow.Object)

task = flow.Parent()

filename = flow.Computed()

def get_filename(self):

project = self.root().project()

store = project.settings.store.get()

task_name = self.task.name()

name = self.name()

ext = '.ma'

return os.path.join(store, project.name(), task_name, name)+ext

def compute_child_value(self, child_value):

if child_value is self.filename:

self.filename.set(self.get_filename())

Note

Here we are using self.root().project() to access the project settings. This is a nice alternative to using many Parent() relations. If you are wondering why not using something like a Project() relation, I’d say you have a point ! We can discuss it in the discord channel :}

After reloading your project definitions you will see how the filename of each File has its own value, and this value comes from a well-isolated functional policy.

The purpose of the File is to be edited, so let’s add an Editor \o/

class EditAction(flow.Action):

_file = flow.Parent()

def get_buttons(self):

self.message.set('<h2>Select an Editor</h2>')

return ['Open with Maya', 'Open in Text Editor']

def run(self, button):

# Here we would select an executable depending on the button

# or the file extension or anything really,

# and use subprocess to run the editor.

print('Editing the file:', self._file.filename.get())

class File(flow.Object):

task = flow.Parent()

filename = flow.Computed()

edit = flow.Child(EditAction)

...

In this oversimplified example the File is used only in the Task, but in real life you’d probably use it in many other situations. Defining it as a component let you later extend it with functionalities like the EditAction or other Persistance Layer features like version management…

Now let’s focus on the Task to see another example of concern isolation: the Status.

Worflows and Pipelines are all about Statuses. Statuses often contain the information used to trigger automations, reporting, etc. And they need to have value among a defined list of possibilities. Let’s add this to our awesome flow !

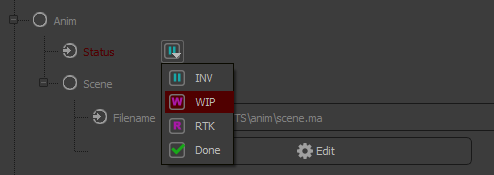

First, we’re going to use a ChoiceValue as we want to restrict the possible values:

class TaskStatus(flow.values.ChoiceValue):

CHOICES = ['INV', 'WIP', 'RTK', 'Done']

class Task(flow.Object):

status = flow.Param('INV', TaskStatus)

scene = flow.Child(File)

This changes the GUI representation of the Task’s status field to a drop down menu:

Note

Kabaret provides default icons for many situations and this is what you see here. This is managed by the kabaret.app.resources module and you can override and/or extend the icons as much as you want.

Second, we want to trigger something when the Status changes. That’s what Statuses are meant for. But the particular details of what should be triggered depend on what the Status is bound to, so we are going to delegate it to the parent Task:

class Task(flow.Object):

status = flow.Param('INV', TaskStatus).watched()

scene = flow.Child(File)

def child_value_changed(self, child_value):

if child_value is self.status:

self.send_mail_notification()

def send_mail_notification(self):

# If this was a real task there would be an assignee

# that we could send a mail to...

print(

'Mailing to santa: status of Task {!r} is now {!r}'.format(

self.oid(), self.status.get()

)

)

And last, we want to report the Tasks statuses into the Shot. This status depends on each Task’s status and should be computed every time a Task status changes. In order to achieve this, we will have the Tasks asking their Shot to update their status when needed:

class Task(flow.Object):

shot = flow.Parent()

status = flow.Param('INV', TaskStatus).watched()

scene = flow.Child(File)

def child_value_changed(self, child_value):

if child_value is self.status:

self.send_mail_notification()

self.shot.update_status()

def send_mail_notification(self):

# If this was a real task there would be an assignee

# that we could send a mail to...

print(

'Mailing to santa: status of Task {!r} is now {!r}'.format(

self.oid(), self.status.get()

)

)

class Shot(flow.Object):

first = flow.IntParam(1).watched()

last = flow.IntParam(100).watched()

length = flow.Computed()

anim = flow.Child(Task)

lighting = flow.Child(Task)

comp = flow.Child(Task)

status = flow.Param('NYS').ui(editable=False)

def update_status(self):

status = 'WIP'

statuses = set([

task.status.get()

for task in (self.anim, self.lighting, self.comp)

])

if len(statuses) == 1:

status = statuses.pop()

self.status.set(status)

...

We could have used a Computed relation for the Shot’s status but this time we chose a simple Param (that the user cannot edit) and we update its Value directly when a Task status changes. The best strategy to use will depend on your case and your fondness…

There’s a last thing you may want to do: Give a hint of the Shot’s status in the Shots list. That requires two lines to add to the Shots class:

class Shots(flow.Map):

add_shot = flow.Child(AddShotAction)

@classmethod

def mapped_type(cls):

return Shot

def columns(self):

return ['Name', 'Ranges']

def _fill_row_cells(self, row, item):

row['Name'] = item.name()

row['Ranges'] = '{}->{}'.format(item.first.get(), item.last.get())

def _fill_row_style(self, style, item, row):

style['icon'] = ('icons.status', item.status.get())

Wooh ! Icons \o/

Conclusion¶

We’ve seen that the concept of extending Objects with Relations to other Objects is pretty simple to understand and to use. And it can efficiently build almost anything using only Params, Actions and Maps.

There’s more in the toolbox, like Refs which are Values pointing to other Objects, ConnectActions that let you react to Drag’N’Drop in the GUI, Relation configuration that let you control their GUI representation, etc.

kabaret.flow has been used in small projects like commercials with ~10 shots and a team of ~10 artists, as well as feature movies with hundreds of shots and complex production tracking tools.

What are you going to use if for ? :D

Here is what we built in less than 150 lines of simple code:

(the menu you see in the upper-right corner is popped up by a RMB on the page path)

Of course, in real life, pipeline management is about doing quick and dirty stuff. That’s the cool thing about kabaret.flow: you can do robust and well-prepared things, but it’s not mandatory and you can also do bad things whenever you want/need. We’ll assume you don’t need any tutorial for that ^.^

Final Code¶

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 | from __future__ import print_function

import os

from kabaret import flow

class EditAction(flow.Action):

_file = flow.Parent()

def get_buttons(self):

self.message.set('<h2>Select an Editor</h2>')

return ['Maya', 'Sublime']

def run(self, button):

# Here we would select an executable depending on the button

# or the file extension or anything really...

# and use subprocess to run the editor.

print('Editing the file:', self._file.filename.get())

class File(flow.Object):

task = flow.Parent()

filename = flow.Computed()

edit = flow.Child(EditAction)

def get_filename(self):

project = self.root().project()

store = project.settings.store.get()

task_name = self.task.name()

name = self.name()

ext = '.ma'

return os.path.join(store, project.name(), task_name, name)+ext

def compute_child_value(self, child_value):

if child_value is self.filename:

self.filename.set(self.get_filename())

class TaskStatus(flow.values.ChoiceValue):

CHOICES = ['INV', 'WIP', 'RTK', 'Done']

class Task(flow.Object):

shot = flow.Parent()

status = flow.Param('INV', TaskStatus).watched()

scene = flow.Child(File)

def child_value_changed(self, child_value):

if child_value is self.status:

self.send_mail_notification()

self.shot.update_status()

def send_mail_notification(self):

# If this was a real task there would be an assignee

# that we could send a mail to...

print(

'Mailing to santa: status of Task {!r} is now {!r}'.format(

self.oid(), self.status.get()

)

)

class Shot(flow.Object):

first = flow.IntParam(1).watched()

last = flow.IntParam(100).watched()

length = flow.Computed()

anim = flow.Child(Task)

lighting = flow.Child(Task)

comp = flow.Child(Task)

status = flow.Param('NYS').ui(editable=False)

def update_status(self):

status = 'WIP'

statuses = set([

task.status.get()

for task in (self.anim, self.lighting, self.comp)

])

if len(statuses) == 1:

status = statuses.pop()

self.status.set(status)

def child_value_changed(self, child_value):

'''

Called when a watched child Value has changed.

'''

if child_value in (self.first, self.last):

# We invalidate self.length whenever self.first or self.last

# changes:

self.length.touch()

def compute_child_value(self, child_value):

'''

Called when a ComputedValue needs to deliver its result.

'''

if child_value is self.length:

self.length.set(

self.last.get()-self.first.get()+1

)

class AddShotAction(flow.Action):

_shots = flow.Parent()

shot_name = flow.Param('shot000')

first_frame = flow.IntParam(1)

last_frame = flow.IntParam(100)

def get_buttons(self):

return ['Create Shot', 'Cancel']

def run(self, button):

if button == 'Cancel':

return

# Real life scenario should validate this value:

shot_name = self.shot_name.get().strip()

# Create the shot using our Parent() relation:

shot = self._shots.add(shot_name)

# Configure the shot with requested values:

shot.first.set(self.first_frame.get())

shot.last.set(self.last_frame.get())

# Tell everyone that the Shots list has changed

# and should be reloaded:

self._shots.touch()

class Shots(flow.Map):

add_shot = flow.Child(AddShotAction)

@classmethod

def mapped_type(cls):

return Shot

def columns(self):

return ['Name', 'Ranges']

def _fill_row_cells(self, row, item):

row['Name'] = item.name()

row['Ranges'] = '{}->{}'.format(item.first.get(), item.last.get())

def _fill_row_style(self, style, item, row):

style['icon'] = ('icons.status', item.status.get())

class ProjectSettings(flow.Object):

store = flow.Param('/tmp/PROJECTS')

framerate = flow.IntParam(24)

image_height = flow.IntParam(1080)

image_width = flow.IntParam(1920)

class Project(flow.Object):

shots = flow.Child(Shots)

settings = flow.Child(ProjectSettings)

|